In just a few years, Korean golfer Inbee Park will take her rightful place in the World Golf Hall of Fame. When she does, Park will become the only Hall of Famer with an Olympic gold medal in golf, which she captured at the 2016 Summer Games in Brazil. She will not, however, be the only Hall of Famer with an Olympic gold medal. Park will share that distinction with none other than Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias.

Zaharias captured two gold medals at the 1932 Olympic games in Los Angeles in track and field. Widely regarded as one of the best female golfers of all time, Zaharias is equally recognized as one of the greatest all-around athletes in U.S. history. The Olympic Games were the grandest stage to showcase her skills, and even proved fortuitous in helping launch her golf career.

During the run-up to the Olympics, Zaharias demonstrated some of the prowess which would soon propel her into folk hero status. In what reporter George Kirksey called “the most amazing series of performances ever accomplished by any individual, male or female, in track and field history,” Zaharias destroyed the competition at the AAU National Track and Field Championships in Evanston, Illinois. She competed in eight of 10 possible events, collecting six gold medals and breaking world records in three of the Olympic trial events: javelin, 80-meter hurdles, and the high jump. Perhaps the most impressive part of her national championship is that Zaharias accumulated 30 points in the competition as the lone member of her “team,” the Employers Casualty Company. The second-place team, the 22-member Illinois Women’s Athletic Club, finished with 22 points.

At the 1932 Olympic Games, there were only five individual track and field competitions for women. Olympic rules prohibited female competitors from entering more than three events. With only 43 women on the American team compared to 357 men, there were obviously fewer opportunities for women such as Zaharias to showcase her talents. Forced to choose, she picked the three events she dominated in Evanston: javelin, 80-meter hurdles, and the high jump. As would be expected from Zaharias, however, attention would follow.

Early on in her sporting career, Zaharias developed a reputation for showmanship, self-promotion, and boastfulness that might make even Muhammed Ali blush. Zaharias didn’t just think she was going to beat you, she told you she would beat you. She basked in the attention, and while many of her competitors grew to resent Zaharias, she was not fazed. The press fell in love with her honesty, wit, and charm, and knowing that stories about her sold newspapers only encouraged Zaharias to play up this side of herself.

In the javelin event, Zaharias set a new world record on her first attempt (143.5 feet) despite tearing cartilage in her throwing shoulder on the toss. Her next two attempts were both for less distance, and although her German competitors thought she was just toying with them, she still held on to win the gold medal. A few days later in the 80-meter hurdle event, she beat fellow American Evelyne Hall by a fraction of a second, setting a new world record in the process at 11.7 seconds. Hall believed she, not Zaharias, had won the race and had the tape marks on her neck to prove it. Officials later concluded that the race was at least a tie, but a protest could not be filed since they were both from the same country. Hall later said that “Babe had so much publicity, it was impossible to rule against her.”

In the high jump event, Zaharias had to settle for a silver medal after some controversy on her final attempt in the playoff against Jean Shiley. Zaharias used a Western Roll to clear the bar – which had been allowable prior to the 1932 games – but since her feet did not go first, the “dive” jump was ruled illegal. So instead of sweeping gold, Zaharias instead came away with two golds and one silver, but just as importantly, grabbed the spotlight in Los Angeles and never let it get away.

Journalist Grantland Rice, one of Babe’s biggest media proponents, declared that “‘The Babe’… is without question, the athletic phenomenon of all time, man or woman.” Rice played a part in introducing Zaharias to the next great passion of her life: golf. The day after her high jump event, Rice invited Zaharias – at the time a relative novice – to play a round of golf at the Brentwood Country Club. Paired together, they won their best-ball match against three other golfers, setting in motion the next phase of a legendary career.

Travis Puterbaugh is the Curator of the World Golf Hall of Fame & Museum in St. Augustine, Florida. He graduated from Loyola University of New Orleans with a B.A. in Communications, the University of South Florida with an M.A. in History, and has worked in the museum industry for 14 years. Travis considers getting to walk inside the ropes during Day One of the 2016 International Crown as the highlight of his time working for the Hall of Fame. Follow Travis on Twitter at @WGHOFCurator.

Travis Puterbaugh is the Curator of the World Golf Hall of Fame & Museum in St. Augustine, Florida. He graduated from Loyola University of New Orleans with a B.A. in Communications, the University of South Florida with an M.A. in History, and has worked in the museum industry for 14 years. Travis considers getting to walk inside the ropes during Day One of the 2016 International Crown as the highlight of his time working for the Hall of Fame. Follow Travis on Twitter at @WGHOFCurator.

Editor’s Note: This article is one of an excellent series of articles by Travis Puterbaugh and the World Golf Hall of Fame & Museum describing the stories and background of women’s golf artifacts and displays from the Museum’s collection. See the complete series here.

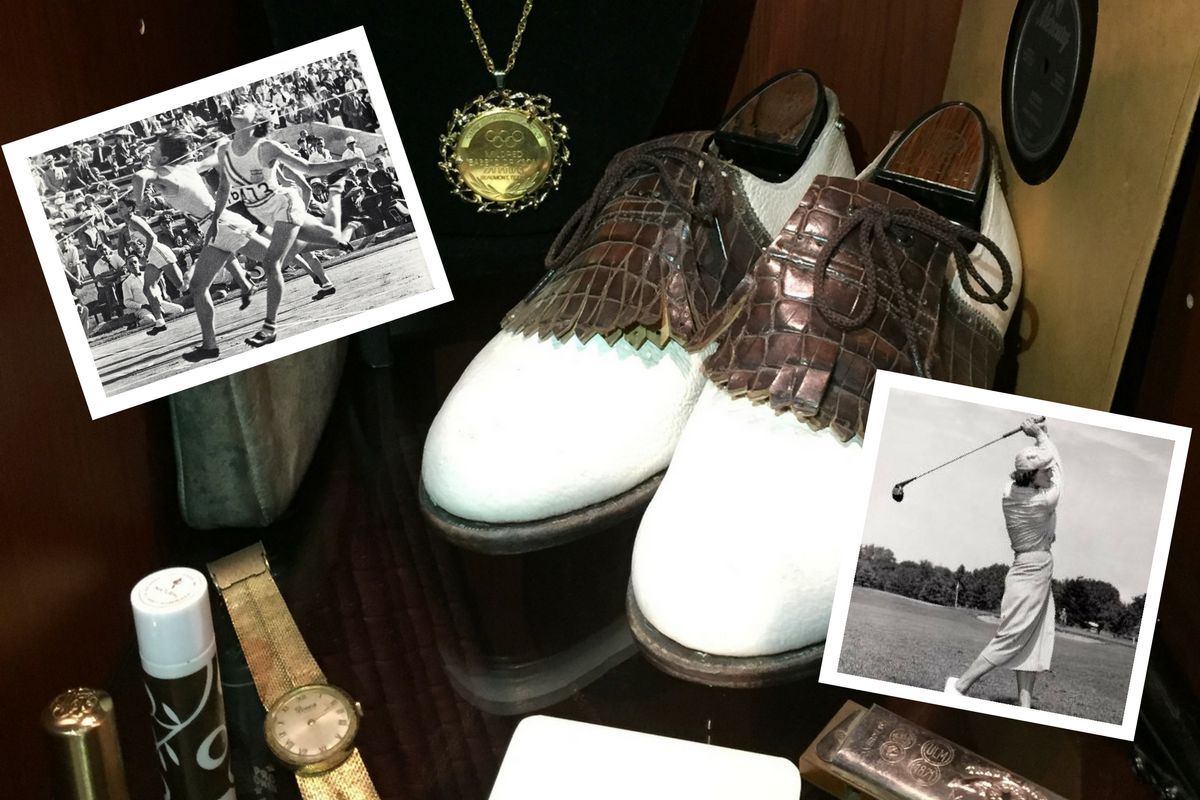

Feature Photo: The museum display for Babe Zaharias containing the commemorative gold medallion given as a gift to Bob Hope from Colonel W.L. Pate, Sr., and Ben Rogers, in 1976 at the opening of the Babe Zaharias Museum in Beaumont, Texas. Medallion donated by the Bob & Dolores Hope Foundation to the World Golf Hall of Fame & Museum.